FOOD LANDSCAPES OF SQUIRREL HILL

CARNEGIE MELLON UNIVERSITY, FALL 2021

Urban Traces Seminar

Instructed by Tommy CheeMou Yang

Fall 2021

A video analysis of Squirrel Hill.

A video analysis of Squirrel Hill.

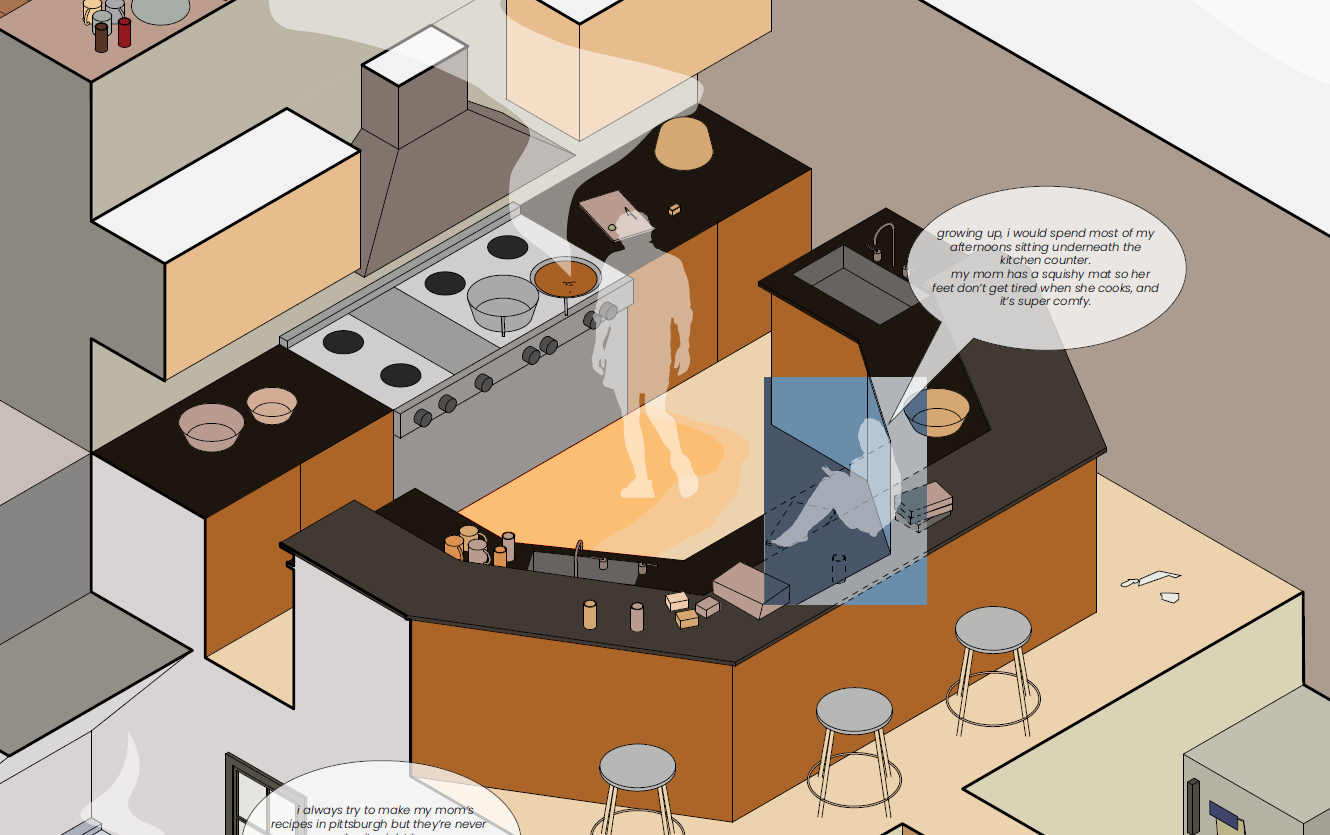

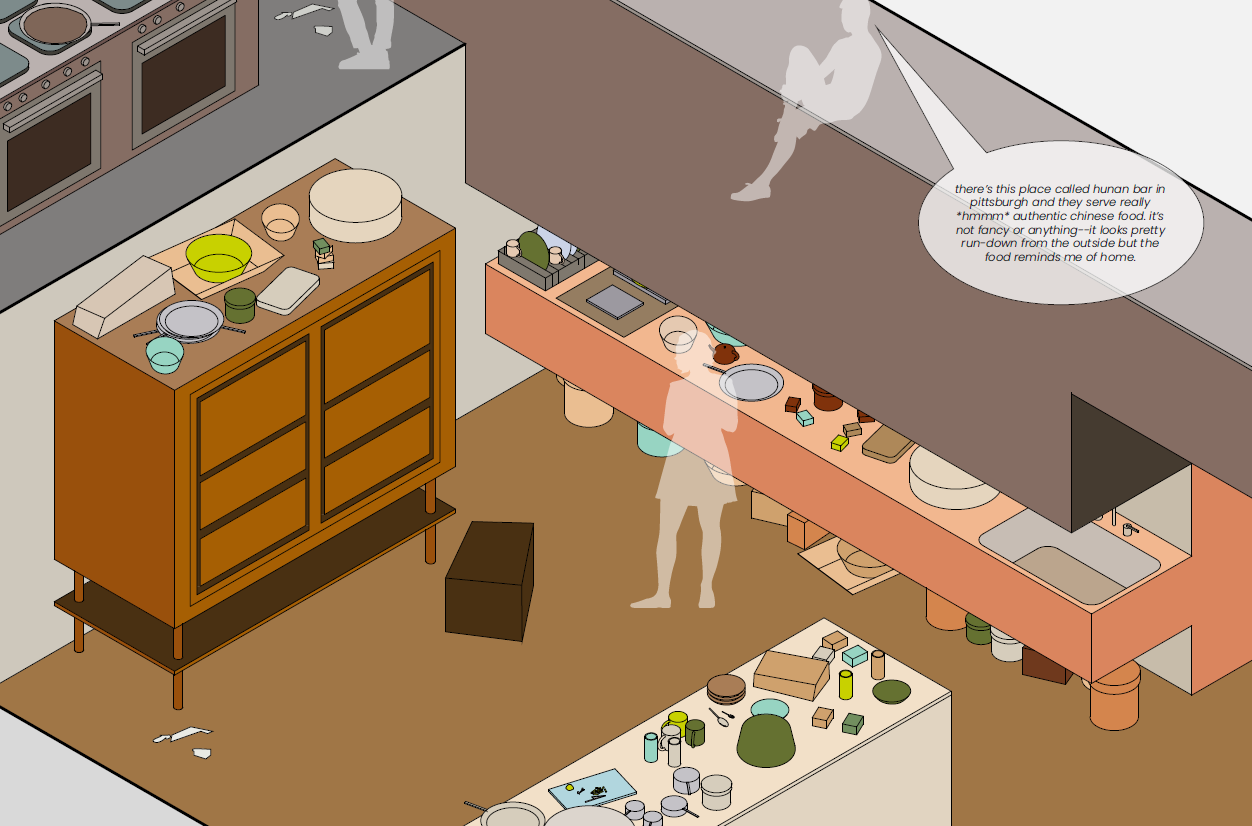

Kitchen matrix.

Squirrel Hill as a neighborhood functions as a locus for transitory bodies from all over the world, from the grey squirrels which skitter on the ground to the birds who visit on their path up the Atlantic Flyway to immigrants from China, Japan, Vietnam, Korea, Mexico, and Thailand, to name a few. These populations navigate a historically affluent neighborhood, deemed as grade A and B (“best” and “still desirable”) in Pittsburgh’s 1937 redlining report. Squirrel Hill's welcoming neighborhood feel is also the result of exclusionary measures that denied black Pittsburghers entry due to redlining and imminent domain policies. “Model'' minority communities such as the asian and jewish populations of Pittsburgh originally were segregated to live exclusively in the Hill District, but eventually gained the freedom to expand into Squirrel Hill. Black Pittsburghers did not share this freedom of movement, and were trapped within the aging infrastructure of the Hill District, further closed in by highway construction and rising housing prices. The effects of this segregation can still be seen today. The story of Squirrel Hill is inextricably linked to subjugation of black communities, and the proliferation of the lasting effects of slavery in the United States. For the Urban Traces Seminar, I have explored how immaterial rituals like food practice can create a sense of belonging, space-take and become an active tool of placemaking. Throughout the semester, I mapped the neighborhood at multiple scales as well as interviewed three stewards of the neighborhood to give us a small glimpse of Squirrel Hill in one semester’s work.

A Brief Timeline of Squirrel Hill.

For residents of Squirrel Hill, rituals around food -- including going to the grocery store, selecting ingredients, prepping, cooking, and eating -- create and recreate powerful memories, from reminders of childhood to the unquantifiable feeling of being home. Food practices occur in everyday ephemeral bodily experiences, heightening senses of smell, taste, and sound that are immeasurable, but part of the rhythms of people’s daily lives. According to Arjit Sen in his essay Eating Ethnicity: Spatial Ethnography of Hyderabad House Restaurant on Devon Avenue, Chicago these sensory experiences become a memory-charged sign encoded with recreated, and familiar space, and can transport the mind across time and space. A good meal also has the power to connect people of a wide range of backgrounds and experiences, and can help bridge gaps in cultural differences.

Murray Avenue.

This reading of food as a spatial actor leans heavily on Jie Li’s book on Shanghai Homes, as preparing food fundamentally recreates place inside of new domains. Within each recipe is inscribed generations of historical knowledge and practice which are revived and augmented with each iteration. The act of cooking is inherently a corporeal practice, specifically an incorporating ceremony of the body, as described in Paul Connerton’s book How Societies Remember published in 1989 work. Preparing a dish becomes automatic and corporeal as the steps and rituals involved are (re)produced and (re)inscribed each time they are made. The dishes are also altered from generation to generation, and from place to place. Depending on the availability of ingredients and the knowledge and preferences of the chef, dishes change and are never the same twice. Dishes passed down for generations contain the traces of the past written into their flavor profiles. In addition, the act of cooking can become a radical act of space-taking, placemaking for those that are not otherwise offered a place of their own, and food creates opportunities to embed one-self to the in-betweenness of society, existings liminally, to borrow terminology from Ana Luz in her essay Places In-Between: The Transit(tional) Locations of Nomadic Narratives.

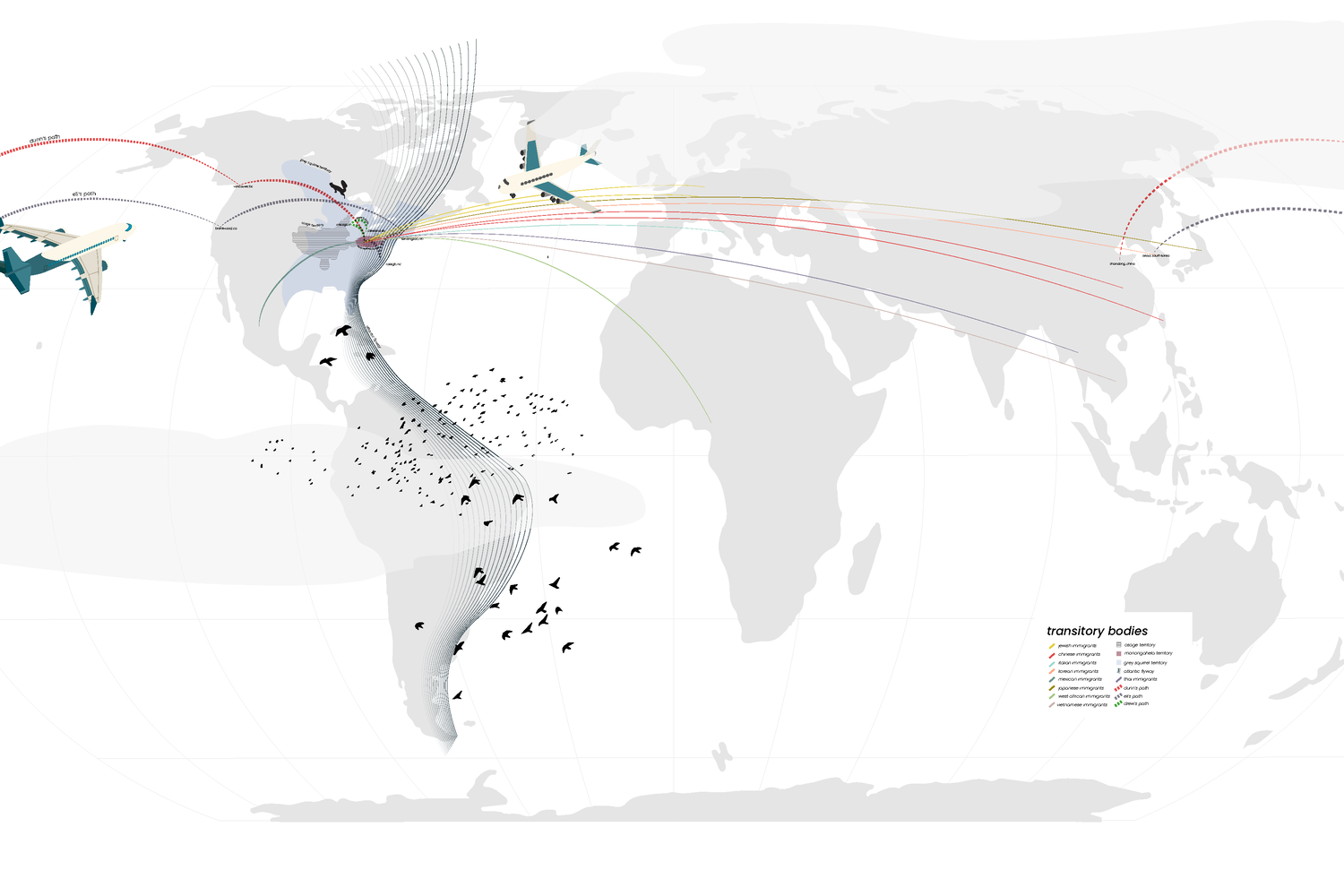

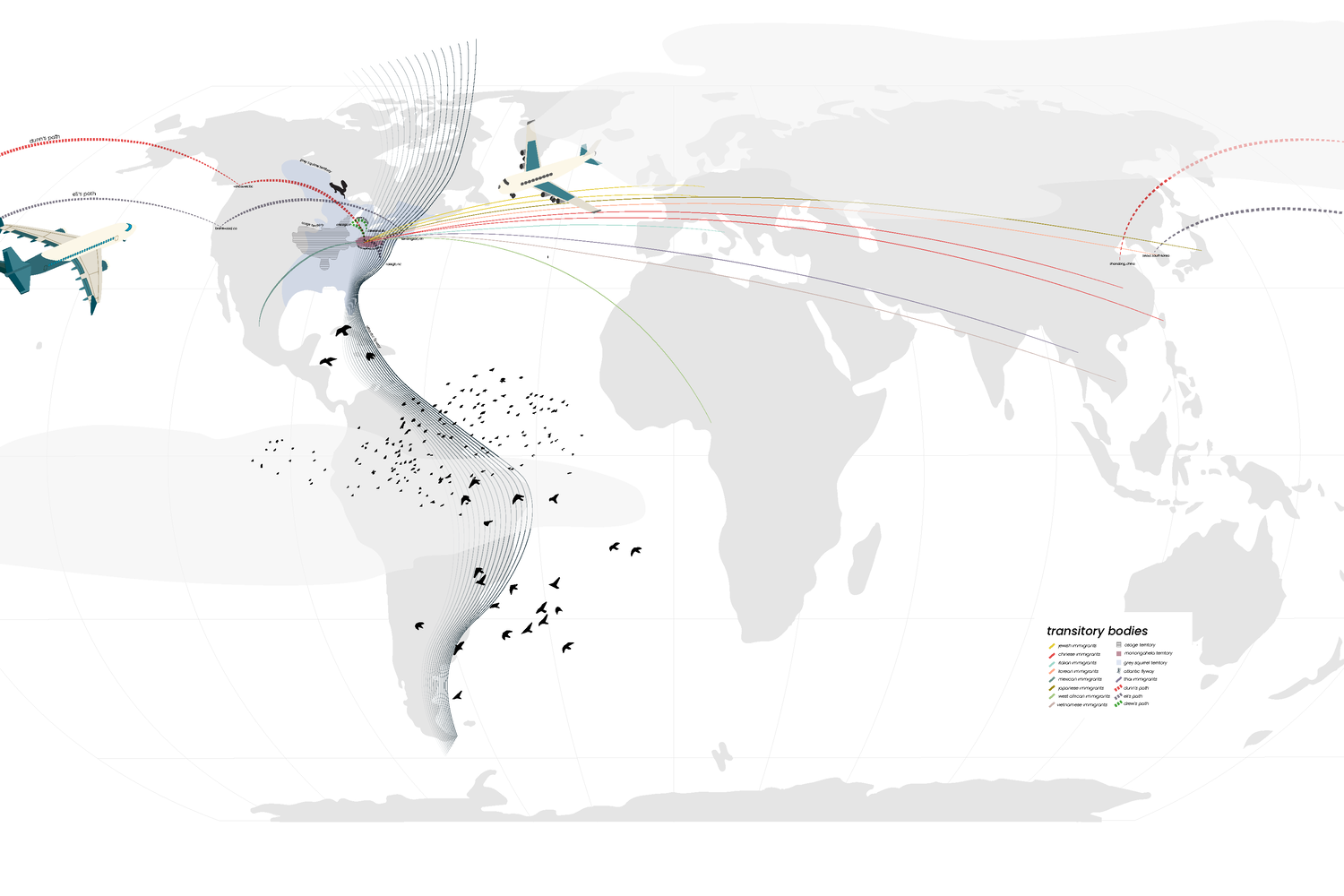

Transitory Bodies.

For Squirrel Hill in particular, cuisine is a driving force for community interaction, and becomes a way to foster civic belonging in the togetherness and a general feeling of belonging for everyone in the neighborhood. As one of Pittsburgh's most diverse neighborhoods, Squirrel Hill nurtures a growing population of Jewish and East Asian population in the city drawing students from the University of Pittsburgh, Carnegie Mellon, Chatham, and many more adjacent institutions to Squirrel Hill, who travel here to get the taste of “home” they so crave. This home is not a physical location, but rather a collection of feelings that references belonging, safety, and comfort--a space rather than a place. The food landscape in the neighborhood makes them feel less alone. This atmosphere is palpable in Squirrel Hill, from restaurant interiors to the amalgamation of smells that waft from their kitchens--mixing spices and flavor profiles from all around the globe. The jewish population in this neighborhood uses food spaces, particularly Murray Avenue Grill as a safe gathering place for the entire community. The close nature and walkability of Squirrel Hill becomes especially important for Jewish communities, who rely on amenities--such as kosher groceries and delis, worship spaces, and community gathering halls--within walking distance due to restrictions on driving during Shabbat. The growing asian community of students and young families can find international ingredients locally at Panda Mart, or can pick up familiar homestyle cooking at any of the numerous restaurants. The food of Squirrel Hill creates strong ties from this neighborhood to places all over the world. Walking down Murray Avenue, anyone can grab any number of different cuisines, from west african to thai to traditional jewish cuisine.

Multi-scalar connections.

Food practices are not just nostalgic forces which incorporate the past however; as food creates an embodied form of placemaking, weaving interactions within Squirrel Hill that might not otherwise be common. In this way, Squirrel Hill becomes a locus for transitory bodies which fosters relationships across community lines, and contributes to the neighborhood's safe and welcoming atmosphere, where orthodox jewish families coexist with latino, asian, and (some) black communities, grappling with their differences as they live side by side. Squirrel Hill, due to high jewish populations, is also the site of severe acts of anti-semetic violence, most notably the murder of rabinical student Neal Rosenblum in 1986, and the Tree of Life massacre shooting in 2018. As a result of this, the ability to carve space through the reproduction of traditional and culturally significant food practices becomes essential to the resiliency of the neighborhood and the jewish community as a whole. Food practice becomes a counter-hegemonic act of worldmaking which allows communities to hack the neighborhood and carve a space that is uniquely their own.

Kitchen vignettes.